State Department Underscores Human Rights Abuses of Key US Ally in Africa

The just-released 2012 Human Rights Practices country report for Ethiopia, compiled by the US State Department, confirms an uncomfortable fact—most US government officials are aware of the repressive nature of Ethiopia’s US-backed regime. The State Department document recognizes reports of unlawful (politically-motivated) detention, instances of torture, political use of the 2009 Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, and the often-unchecked use of force by the national security forces. Yet, Ethiopia remains among the largest recipients of US aid in Africa. Ethiopia receives on average $3 billion in annual development assistance from international funders—with an average of $800 million coming from the US. Why, then, do development aid officials resist calls for rigorous and independent investigations into how these funds are used and also dismiss charges of forced resettlement and the “political capture” of development assistance by the Ethiopian ruling party?

Although the State Department document contains some understatements and factual inaccuracies, it is significant as it outlines not only cases of human rights violations, but also the Ethiopian “architecture of repression” that results in the curtailment of human rights while undermining attempts by local and foreign journalists and investigators to assess the extent of the repression.

ROLE OF SECURITY FORCES

Each state in Ethiopia has special police forces, and the State Department report suggests that security forces and militia groups operate in many cases as “extensions” of political bosses in the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). There are few known mechanisms for investigation of these forces and the results of investigations that are conducted are rarely made public. However, it seems clear that the deployment of security forces is often politically motivated, aimed at stifling political dissent. The State Department report concludes: “Security forces continued to detain family members of persons sought for questions by the government.” It adds more broadly that there were allegations of “killings . . . torture, beating, abuse, and mistreatment of detainees.” In addition to enabling the government’s political hegemony, the security forces have been used to intimidate religious and ethnic minorities. The report found that in July 2012, security forces “used force and arrested” Muslims protesting alleged government interference in religious practices.

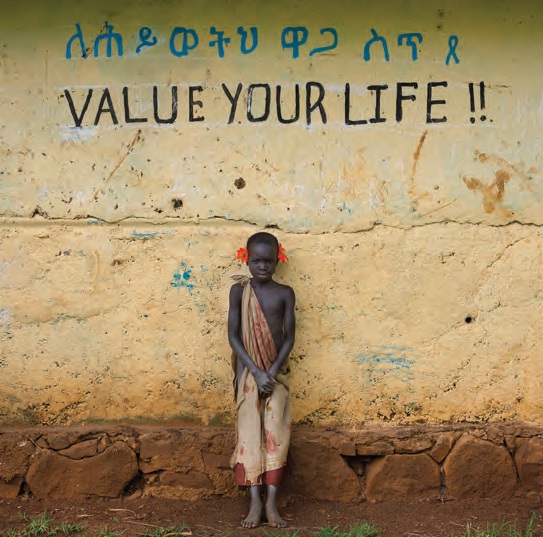

A Suri man who was wounded by security forces.

CULTURE OF FEAR

The findings in the State Department report illustrate that the Ethiopian government’s human rights abuses are aimed not simply at punishing political dissenters, but also at creating an environment less conducive to critique—a culture of fear. The report illustrates how the repressive Charities and Societies Proclamation (CSO law) and the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, both passed in 2009, are used as a tool to quell dissent and to prevent independent investigations. According to the State Department’s report, the CSO law places significant operational and funding restrictions on organizations “that advance human and democratic rights or promote equality of nations, nationalities, peoples, genders, and religious; the right of children and persons with disabilities; conflict resolution or reconciliation; or the efficiency of justice and law enforcement services.” Under the CSO law, which among other things prohibits the operation of any NGO or CSO that receives over 10 percent of its funding from foreign sources, 10 CSOs have been closed and the Ethiopian government issued warnings to an additional 476 CSOs.

The State Department report found that the Ethiopian government tried 31 people this year under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation. According to the report, those tried included “12 journalists, opposition political figures, and activists based in the country, as well as an Ethiopian employee of the UN. All were found guilty.” 21 were tried for their involvement in protests. The State Department report states that evidence in these trials was often “indicative of acts of a political nature rather than linked to terrorism.” This is perhaps most blatantly clear in the arrests and sentencing of journalist Eskinder Nega; the vice chairman of the government’s opposition front, Medrek Audualem Arage; and Natnael Mekonnen, an officer of the Unity for Democracy and Justice Party. All three were found guilty of terrorism and treason. While Nega and Mekonnen received an 18-year sentence, Arage received a life sentence in prison. As the State Department report illustrates, this crackdown on journalists is no secret. Just recently, the imprisoned Ethiopian journalist Reeyot Alemus was awarded the 2013 UNESCO World Press Freedom Prize.

If politicians and journalists aren’t immune to politically motivated human rights abuses, it should not be surprising that these extend to the Ethiopian population at large. The State Department found that the “government reportedly used a widespread system of paid informants to report on the activities of particular individuals.” When placed alongside allegations that the government’s violent resettlement program targets prime land for investment, the political and economic use of these informants is not just propelled by party interests, but also investors and the promoters of large-scale agriculture as a path to development. This form of hidden and systemic suppression of dissent creates the culture of fear that can discourage political contestation around land grabs. Just last October, the State Department reported, Ethiopian police “arrested seven individuals after they gave radio interviews regarding reported land grabs in Lega Tofo in the Oromia Region.” Although they were later released, Ethiopians critical of government policies are often subjected to this type of intimidation as well as restricted access to employment and education—this disproportionately affects Ethiopian youth. Specifically, the report found, “unemployed youth who were not affiliated with the ruling coalition sometimes had trouble receiving the ‘support letters’ from their kebeles (neighborhoods or wards) that are necessary to get jobs.” The report later adds that, “the ruling party, via the Department of Education, continued to give preference to students loyal to the party in assignments to postgraduate programs.”

The few investigations conducted by development organizations on the misuse of assistance funds cite “uncorroborated” accounts of violence accompanying villagization schemes. However, these investigations overlook corroborations of such evictions by the Oakland Institute and Human Rights Watch. Additionally, the investigations fail to recognize the culture of fear and threats of violence that inhibit the collection of complaints against the ruling party.

CRACKDOWN ON PRESS FREEDOM

The State Department found that in 2012, at least five major newspapers (including two Muslim newspapers) closed following government pressure. The central government maintains great control over national airwaves as the owner of the only nationwide radio and television stations. In just one year, restrictive press policies have shrunk the weekly circulation of newspapers in Addis Ababa from 150,000 in 2011 to 100,000 in 2012. The report notes that, “government harassment of journalists caused to avoid reporting on sensitive topics.” While independent newspapers exist, the State Department report mentions that press restrictions are made through the Berhanena Selam Printing Press, the government-owned press that accounts for nearly 90 percent of newspaper printing nationwide.

The US and other Western donors have been keen in recent years to avoid direct finance programs involving human rights violations and forced evictions such as the resettlement and villagization program. Yet, by providing as much as $3 billion in annual aid to Ethiopia, by some estimates equivalent to nearly 50 percent of the national budget, they are actually enabling the government’s policies. This hypocrisy stands in stark contradiction with the commitments of US and other Western democracies to promote human rights, democracy, and good governance in the developing world.

For the full text of the State Department’s Human Rights Practices report on Ethiopia, see: http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2012&dlid=204120

Luis Flores is a recent graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, with degrees in Political Economy and History. He is currently an intern scholar at the Oakland Institute.